Modern adventurer

10.02.2022 ProfileGarrett Fisher has set himself a lofty goal: to photograph every non-polar glacier across the globe. Having recently documented the Alps from the cockpit of his 70-year-old plane, which he keeps in Gstaad, Garrett met with GstaadLife to talk glaciers, adventure and how to capture the perfect aerial shot.

Why glaciers?

It’s funny to think that I didn’t even know mountains existed when I was young. I grew up in upstate New York where everything was relatively flat so you can imagine my excitement when I first came across pictures of mountains in a book. Over time I crafted this romantic notion of grand illustrious mountains with glaciers spilling down from 20,000 feet [6,000m] into the sea, complete with bears catching salmon in rivers. While I no longer harbour such idealistic impressions, I still think glaciers take mountains to a whole other level.

What is your connection to the Saanenland?

I keep a plane in Gstaad and spend a lot of time here. Last summer I completed a project to document every glacier in the Alps. This was a huge undertaking as there are over 4,000 of them. From 2018 to 2020, I had slowly chipped away at the glaciers from Altdorf to the Massif du Mont Blanc to Dufourspitze, which contain the largest in the Alps although they are a small surface area. The 2021 portion of the project involved more than 90 hours of flying and took over a month and a half to complete, covering a region from the south of Salzburg, Austria almost to the Mediterranean.

Which came first: pilot or photographer?

I was a pilot first and photographer second. My grandfather took me on my first flight when I was two. The story goes that I didn’t enjoy the experience, but promised my grandfather I would like it when I was four. I remember one random day asking my mother “am I four yet?” When she told me I was, I asked her to call Grandpa and tell him I’d go flying because I’d like it. From that day on I loved it.

I started taking photographs in my teenage years. I had some shots published in a college arts publication and Wired magazine, but it wasn’t until about 2010 that I really got into aerial photography. You need to take a lot of technical factors into account to deal with things like haze and perspective, but from the get-go it was clear I had an eye for this.

I published my first book of aerial photographs in 2013. At the time I had based my airplane at the highest airport in North America. We were surrounded by large mountains – the so-called “fourteeners”, peaks over 14,000 feet [4,400m] – and I wondered how difficult it would be to fly up and photograph them all. I learned that it was hard, but I still did it. The book did pretty well and that was the point at which mountain photography really took off for me.

I understand you fly a really old plane?

I still fly the airplane my grandfather restored in the mid-90s. The exterior fabric was changed, many parts replaced and the engine was completely rebuilt. It may be 70 years old, but things that are considered largely disposable with cars continue to get overhauled and replaced with aircraft. As there’s always a nagging suspicion of what’s going on in the engine, I use optical technology to look inside the cylinders and also send oil samples to a laboratory in the US, where they evaluate every oil change.

I’ve also recently acquired a new airplane as my current one is too limited in terms of fuel and speed for the future flights I’m planning.

Have you ever got into any scrapes?

In 2014 my plane got turned upside down in extreme turbulence when flying over a ridge in Virginia. It was a wild ride – like being in the spin cycle of a washing machine – but I’ve never really had any problems in the mountains. I was once flying around Mont Blanc in 52 knot (100 kilometres per hour) winds, but it wasn’t bumpy. If you do it right, it’s not a problem.

I’ve read you take photographs by sticking a gloved hand out of the plane window. How do you know if you’ve got a quality picture?

I’ve learned to take too many photos because it’s impossible to determine if the camera has got out of focus. I’ve also found I can eliminate a lot of problems if I underexpose the shots and keep the aperture in limited ranges. From a compositional perspective I see the images coming. I almost think the Alps are too easy because everywhere you look is a stunning composition. Finding beauty isn’t hard; it’s all about picking what you want to show.

What’s the most amazing thing you’ve photographed?

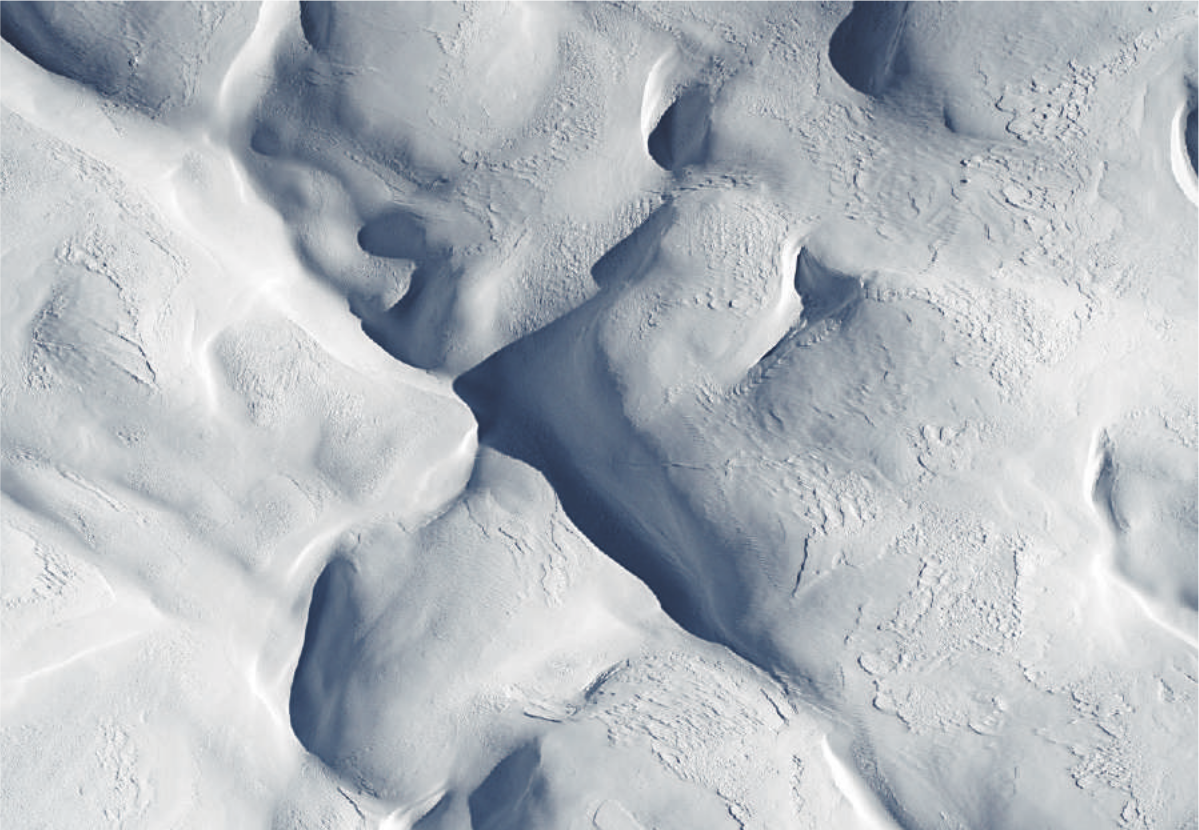

It’s between Konkordiaplatz and Mont Blanc. Konkordiaplatz is part of the Aletsch glacier system, the longest in the Alps, where four major glaciers converge. It’s immense. Looking down on it, at all the texture and contours and seasonal variations you know you’re staring at history. I don’t know when that snow fell but it was a long time ago.

Mont Blanc is so steep and so high that when I’m at the summit looking down on Chamonix it’s as though you can’t even relate to life down below. I’ve visited Chamonix on a number of occasions and when I look up the mountain, I find it hard to believe I’ve flown around its peak.

Was there ever a photograph that got away?

It happened a few days ago. I was flying above the clouds at Interlaken just before sunset. The Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau peaks were largely obscured by cloud, but the view was unlike anything I had ever seen before. It was like forbidden fruit – something you won’t see unless you’re actually up there. I snapped the scene and was in a bubble of joy on the way home anticipating how the photograph would look. But while I see the beauty in that shot, most people prefer another picture I took that day of the mountain range at sunset. While that second photo is an Instagram-worthy visual, the sunset was really just a passing moment in time. It doesn’t begin to capture the unforgettable experience of those shots above the clouds.

You’re often referred to as an adventurer. What does ‘adventurer’ mean to you?

Experiencing glaciers from a small plane is exhilarating, transcendental and spiritually elevating. I go flying because I feel better afterwards and it’s more painful not to.

I don’t see it as dangerous and difficult because I prepare well and make a back-up plan. For instance, if I’m flying to the Jungfrau and my engine quits, I can make it to the closed former airport at Interlaken and land on the grass. I fitted vortex generators in my plane, which means it stalls at very slow speeds, enabling me to touch down as low as about 50 kilometres an hour.

And anytime something scares me, I mitigate. I once got too close to a few gliders so I bought a system that shows me if there are gliders in the air around me. So, I think things through and plan ahead.

What drives you?

During the summer it’s all about documenting the glaciers. There’s a mad dash to get to them when I can. It’s a bit unrelenting but there’s no time to think twice about it.

The rest of the year I’m on the search for something new. For instance we’ve just had 10 days of sun here in the Saanenland. While most people would say that’s gorgeous, I find it a bit tedious to experience the same thing every day. So I’m constantly searching for something new and I almost always find it, whether it’s purple lighting at sunset or something else.

What’s next for you?

My ultimate plan is to document as many of the non-polar glaciers as possible.

This summer I’m heading to Norway for three months. There aren’t as many glaciers there, but they’re really spread out so the distances I’ll have to cover are immense. Then in 2023 I plan to fly to Iceland. That will involve crossing the North Atlantic, which brings a number of additional safety considerations into play. After Iceland I’d like to focus on a handful of glaciers in eastern Turkey near the Iraqi border. Then there’s the biggest peak in Europe at 18,500 feet (5,600 m) in the Caucasus mountains just over the border in Russia. That will require a lot of advance planning and I’ll probably need to take a Russian speaker with me too. Then it’ll be off to Alaska and Canada. I would also like to integrate the southern hemisphere glaciers to double the length of the season – bringing in Patagonia and New Zealand.

I’m faced with many logistical and engineering challenges. When I review insurance policies and see all the places I have no coverage, then realise those are the exact places I want to go, it brings home to me the ambition of my project. But I’ve never said I don’t want to do this. Even in the heat of the most complicated situations when I’ve been exhausted, battling every Covid, bureaucratic and flying rule you could imagine, I still know I have to get this done.

ANNA CHARLES