Rescuer in the snow - and even more snow

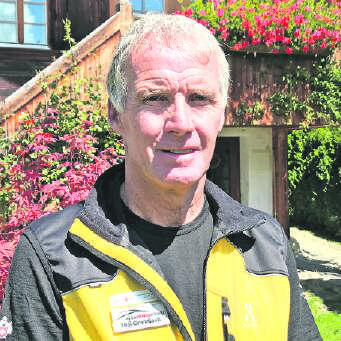

28.12.2021 Gstaad LivingUeli Grundisch led the SAC rescue station in Gstaad for 25 years, a straightforward, quiet and modest person.

Travelling with Ueli Grundisch in the mountains is a real treat. He regales the company with information about rare stone herbs. He asks if you have seen the adder by the wayside and takes a break for a drink before you realise you are thirsty. From now on, he will have more time for the SAC hikes described here because he retired as chief of rescue of the SAC rescue station Gstaad. He will stay on a little, though. The newly elected Simon Bolton asked Grundisch if he could remain in the team as his deputy. Grundisch didn’t have to think about the answer: “Of course I said yes. I can’t just quit after putting so much heart and soul into it!”

“Watch out and listen”

But what does a chief of rescue actually do? “Watch out and listen, day and night,” Grundisch answers the question. Then he turns serious: “You’re responsible for making sure the rescue station is running, that there are enough rescuers and that they receive proper training.” He took this to heart. He noticed that the rescue quality could not be raised to the desired level with only three to four exercises per year because, with the many new trend sports, rescue tactics have also changed. Together with companions Hansruedi Oehrli and Alfred Schopfer, he subsequently invited the team to 12 to 15 exercises per year – and only those who attend at least six of them have since been registered as rescuers.

The Gstaad rescue team meets monthly on a Friday at 6.30 pm. The rescuers blindly tie knots. They bury figurines in the snow and then search for them with probes, avalanche transceivers, and avalanche dogs. The rescuers fly up a mountain hanging on a rope. And they simulate possible missions in the terrain.

The most difficult search

Digital technologies are being used more and more often – also in rescue operations. This means receiving the alarm on the mobile instead of the pager, for example. Grundisch observes this development with mixed feelings. “The whole thing is not yet fully developed,” he says. Too often, there are gaps in mobile reception. Batteries of mobile phones are also a critical element because they can discharge unpredictably fast in the cold. Another reason for his rejection: “It excludes some rescuers because they are not digitally fit enough!”

But digitalisation does have its positive sides, too: The rescue station coordinates operations via a Whatsapp group, which simplifies a lot. And in one case, two people buried in the snow could only be found thanks to mobile phone tracking. The hikers were travelling without avalanche transceivers. Because the only indication of their location was their parked car, the search was difficult and unsuccessful for a long time. “We were fortunate to have found them at all. When we recovered the two bodies, we found that their mobile phone battery was almost empty.” Grundisch does not want to imagine the pictures if the deceased had only been found when the snow melted.

Largest search operation

Grundisch has many memories from his rescue missions, and some of them are neatly sorted in two binders in his office, which is on the sunny side of his chalet in Gruben. The most extensive rescue operation still tingles a little under his skin, even though it happened 18 years ago. On 26 April 2003, a young man of British nationality travelled on foot with his parents. After the Enge in Lauenen, the parents returned to Gstaad. The 18-year-old, however, still wanted to go up the “little” hill and pointed to the Mutthore (2312 m).

“There is no hiking trail to the Mutthore, so the search was arduous,” says Grundisch. Because the missing man was unfamiliar with the area, the rescuers and the police tried to get into his shoes. They assumed that the missing person had chosen a direct route to the Mutthore. So first, they searched in the rain between Lauenen and Lauenensee. But neither the rescuers nor the helicopter nor the search dogs found him.

After the unsuccessful search in the continuous rain, the perimeter was extended to Louwene and Jaas-Chäle. Another team climbed to Rieji below Mutthore. But the search had to be abandoned for safety reasons. An endless night awaited the experienced rescue leader. The next day, they began their search early. Finally, search dogs found the teenager. He had been swept down in a snow slide and had suffered fatal injuries. “The death of this young person has shaken us all.”

A shake of the head and a grin

Whether a rescue moves Ueli Grundisch or not depends on the situation. When a young man died last winter on the Wasserngrat due to an avalanche, the 69-year-old felt more resentment than sympathy. “Warnings about the great avalanche danger were issued on all channels. Nevertheless, and despite a warning from his father, he and two friends rode down a ditch that was far too dangerous. An avalanche broke loose and buried one of the three, a 21-year-old.” Even today, Grundisch is still upset because the young men had not only put themselves in danger by doing so but also the rescuers. “The rescue on the rope of the hovering helicopter was perilous. It even had to be interrupted because of another avalanche.”

Fortunately, Grundisch also has merry tales in store. Last May, the fog alternating with clouds and sun, a couple sent off an alarm. The man and woman were on the traverse between Lauenenhorn and Gifer. Wearing shorts and light hiking boots, they kept slipping on the snow that still lay at that altitude. They had trouble recognising the mountain path, and they were feeling the cold. Grundisch was on the phone with the lost couple. “We want the helicopter!” he heard them say. But the helicopter could not fly because of the poor visibility, so the rescue took a different course.

With the help of a mobile phone photo, Grundisch could locate them and guide them over the phone. When they arrived at the Giferhüttli, they called Grundisch again as promised. The rescuer offered to fetch them by car on the nearby Berzgumm. “No, no!” he got in reply. “Now we’re warm again and hiking home!” The next day, Grundisch received a spontaneous thank-you visit. “That made me very happy! And by the way, I could guide them from the comfort of my office chair with binoculars.”

Now 25 years of “clinging to the pager” are over. “It was a long time, but a good time. I enjoyed a lot of it, and sometimes I got annoyed.” That leaves only one question: “Will there really be more pleasure tours with Ueli Grundisch at the SAC?”

BASED ON AVS/BLANCA BURRI