Depopulation in the Saanenland

23.07.2021 Gstaad LivingNew ways of living and working offer mountain regions like Obersimmental and Saanenland an opportunity. “Creative solutions are needed for success,” says Professor Dr Heike Mayer from the University of Bern.

The centralisation of the past decades has left its mark. The possibilities in cities are disproportionately higher than in mountain regions and attract young people. Jobs, educational institutions, culture and leisure activities, helpdesks, and offices of the authorites are just a few examples. As a consequence, many mountain regions are affected by depopulation.

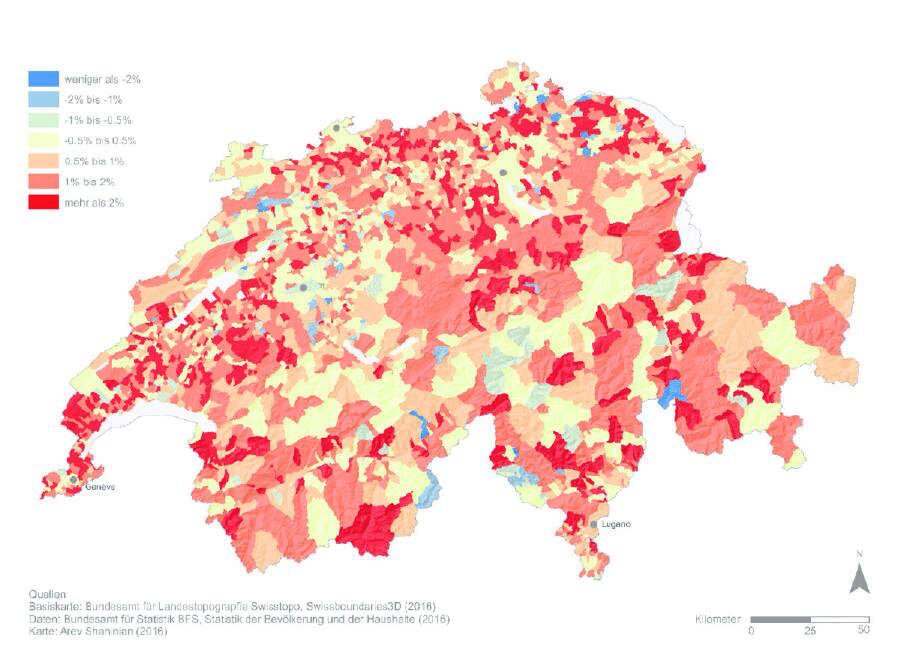

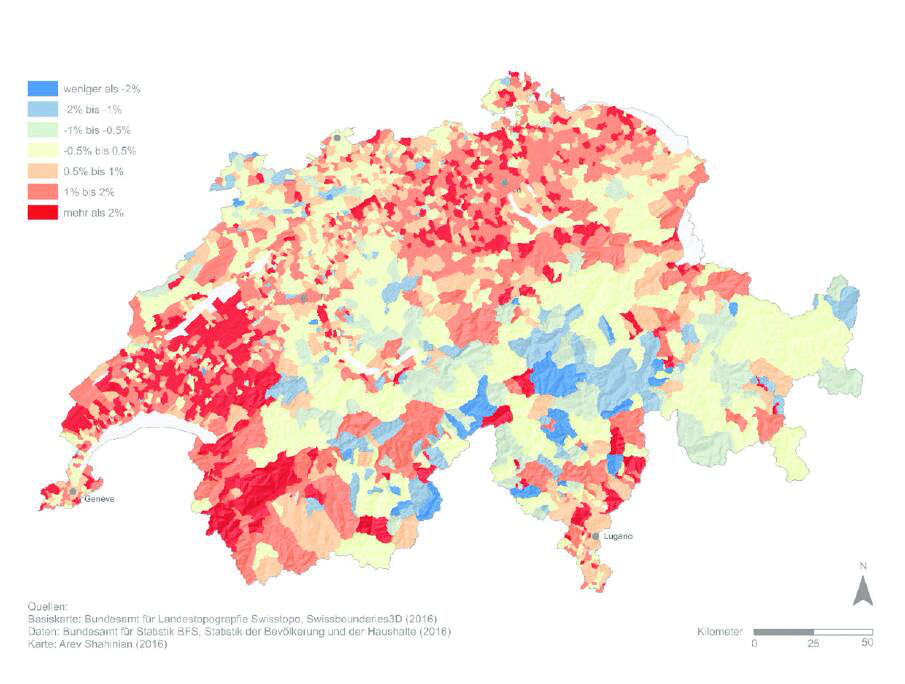

Obersimmental-Saanenland has lost

Obersimmental-Saanenland is not immune to this development. The administrative district lost 1.5 per cent of its permanent resident population between 2010 and 2019. Boltigen is particularly hard hit, with a minus of 9 percent. In Zweisimmen, on the other hand, the population has increased by 4 per cent in the same period. Because housing is relatively expensive in the Saanenland, many families moved to Zweisimmen.

The construction boom of the past decades in the municipality of Saanen might suggest that its resident population has increased. The opposite is the case: from 2010 to 2019, it decreased by 2 per cent and in Gsteig by 1.3 per cent. In Lauenen, on the other hand, it grew by 2.6 per cent.

Countertrend in sight

Many city dwellers have felt the negative sides of city life particularly acutely during the pandemic. The cramped conditions and lack of natural living space for recreation recently led to a boom in property purchases in mountain regions. “The effects of the coronavirus offer mountain regions a certain opportunity,” explains Mayer, head of the Economic Geography Unit at the University of Bern. People want to escape the pandemic by living in the countryside. However, Mayer puts it into perspective: “Not all regions can benefit from the urban exodus.”

Basic services necessary

In order for city dwellers to move to the countryside, they need basic services covered: Shopping facilities, public transport, a functioning health service with GPs or a maternity hospital, schools and jobs as well as culture and leisure activities. “The offer does not have to be as dense and diverse as in a city, but the newcomers must feel cared for and safe,” says the scientist. But even with all of these points covered, the big masses will not move to the mountain regions. “Of course there are people who consciously return to a mountain region, but not in droves,” Mayer emphasises.

As far as infrastructure is concerned, the Saanenland and Zweisimmen have done a good job in recent years. It becomes more difficult for regions where shops, part of the basic services, and leisure facilities have been closed. Mayer: “In communities where jobs and all kinds of offers have been lost, it is very difficult to reestablish them.”

How can new residents be attracted?

Some municipalities that are particularly hard hit by depopulation choose creative and sometimes expensive solutions to attract young families or businesses. “Albinen in Valais offers young families money if they settle in the municipality,” says Mayer. This has worked quite well, she says, and a counter-trend has been initiated.

Multi-local working has a future

Mayer describes multi-local working as a promising opportunity. Instead of commuting to the workplace in the city every day, it makes sense to work at home. However, home office is not everyoneʼs cup of tea, which is why she sees great potential in coworking spaces: “In Meiringen, for example, a former shop was converted into a coworking space, so employees no longer have to commute every day. Of course, she says, this is not suitable for all professions: “Craftsmen, for example, have to work in the workshop or on the construction site.” But positions in creative, project-oriented professions and in the knowledge sector are predestined for multi-local working.

Planning the future

Mayer recommends that mountain regions develop an overall strategy on how to deal with depopulation. This includes a record of the region’s current status, where they want to go and how they will get there. “As a rule, the residential population has different needs than tourists, and this must not be forgotten in the analysis,” she says. Hence it makes sense to include the target groups when working on a strategy: what do young people and families need to feel at ease, what kind of support do young SMEs need to settle in the region, etc.?

It is not only a matter of meeting the needs of the newcomers, but also of considering which competences are already anchored locally. She mentions tourism and mountain farming. These service providers should definitely be included in the development of a strategy against depopulation. If they are on board as partners, a strategy has a much better chance than without them.

A culture of welcome starts in the head

Locals play a major role in this development. Mayer knows enough examples where newcomers have moved away again after a short time. “All efforts only work if the newcomers feel a culture of welcome,” says the scientist. “Newcomers usually want to integrate and get involved. In the parish council, in the school board or in various associations.” However, she advises, people from another region often bring new ideas, which the local population should listen to and implement with a certain openness.

The current corona-related trend can give mountain regions hope that young families will move to the countryside. However, successful integration depends on many factors: housing, employment, infrastructure, recreational opportunities, childcare, nighlife and cultural offers and, last but not least, a culture of welcome.

BASED ON AVS/BLANCA BURRI