K

18.12.2019 ProfileAn exhibition in the museum in Saanen last summer revived his name and his teachings and has now been extended to last over the winter 2019/20. Friends who, with others, run an educational trust explain who this remarkable personality was, what he taught and why he is still relevant today.

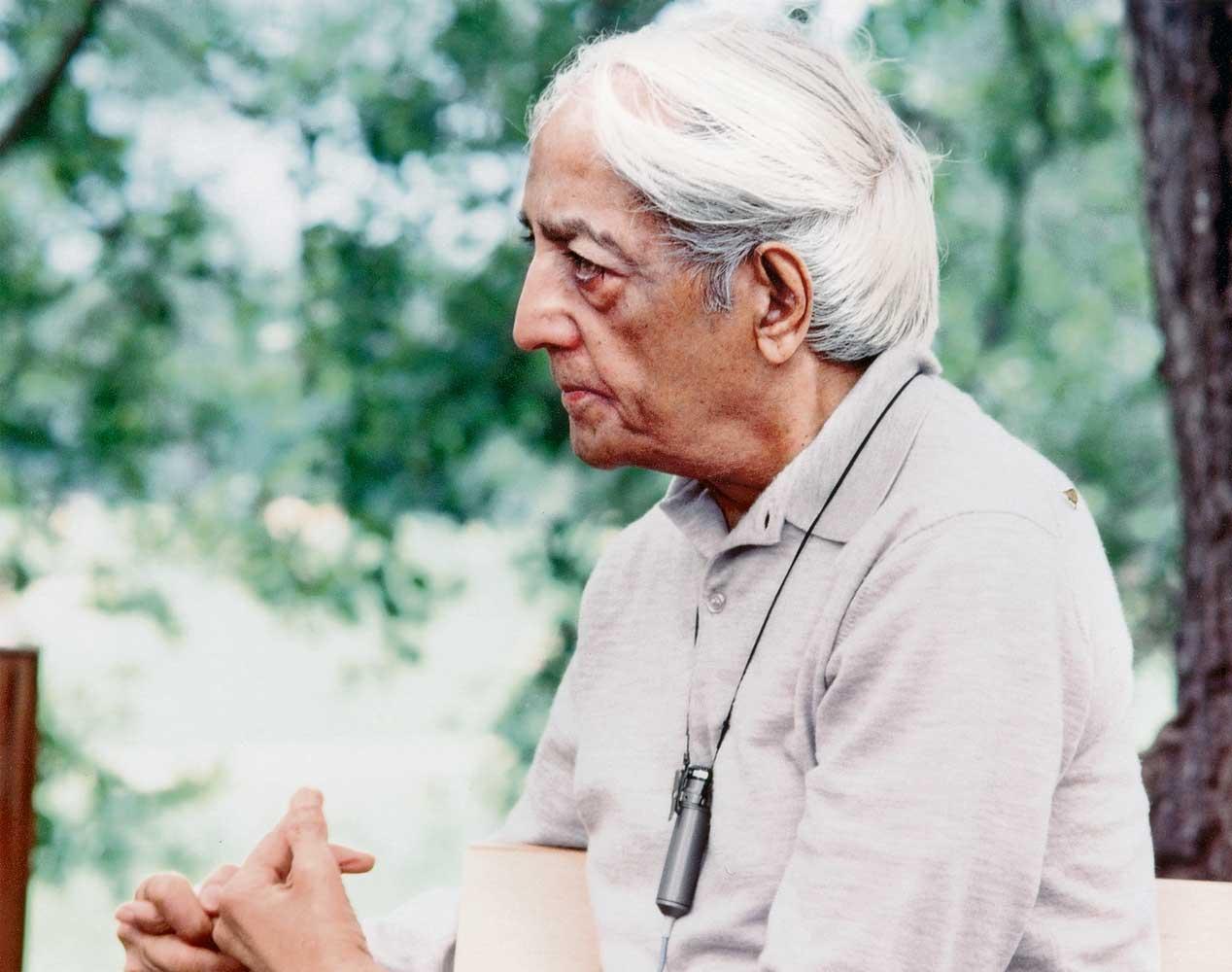

Krishnamurti was a world-renowned educator and philosopher. His more than 70 years of talks and dialogues have been published in over 80 books in dozens of languages, with millions sold. Hundreds of audio and video recordings subtitled in many languages can be accessed freely online. Please tell us more about him.

Listening to him or, for example, reading Krishnamurti’s Notebook, one can tell that he had an extraordinary relationship with nature and that there was a sense of timelessness about him; the appalling suffering in the world never failed to move him. He watched events closely, especially in terms of the human mind in action, and engaged in dialogues of exploration with anyone who was interested. He pointed to humanity’s psychological conditioning, to the illusions that separate us from nature (or appear to) and divide us as a species, turning person against person. He often asked if we were actually seeing what was happening or merely conceptualising and believing that we were seeing. He stated that profound insight into human consciousness could transform the world. And, as each person is an embodiment of the whole, each of us, in whatever state, affects the whole.

Can you introduce yourselves and describe the organizations founded by Krishnamurti?

Krishnamurti established four foundations to maintain archives, publish books and oversee six (now eight and counting) schools. We – Claudia Herr, Javier Gómez Rodríguez and Jürgen Brandt – were on the staff at one of the schools, Brockwood Park in England. Helped by Friedrich Grohe in Rougemont, we began considering how it might be possible to highlight Krishnamurti’s work in Saanen.

Friedrich had a friendly relationship with Krishnamurti – K – during the final three years of K’s life and is the author of The Beauty of the Mountain – Memories of J. Krishnamurti. This book, available in several languages, is a good introduction to what K talked about. Friedrich is an honorary trustee of the foundations and helped us set up the A G Educational Trust which supports certain Krishnamurti education projects.

What was Krishnamurti’s relationship to the Saanenland?

In summer 1957 a local resident, Mme Safra, invited him to spend some time here and he fell in love with the light, the mountains, meadows and streams. He gave public talks in Saanen in 1961 at the Grosses Landhaus, which held 350 people; additional meetings were also held at the Bellevue Hotel in Gstaad. The Saanen Gatherings would continue for another 24 years.

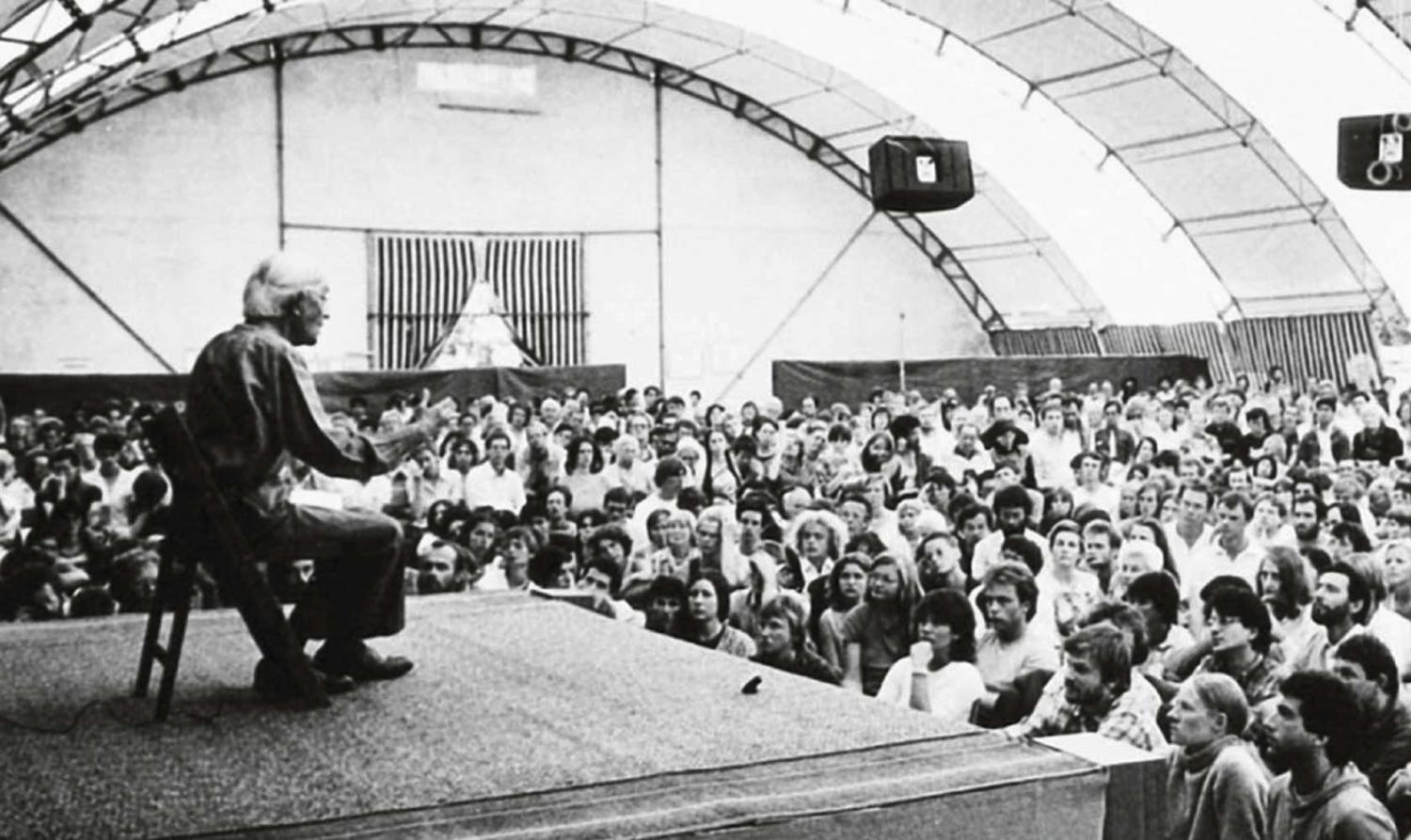

Each summer from 1962 to 1967 they took place in a temporary pavilion that held 900 people, situated first on the Saanen airstrip then on the football pitch on the other side of the river from the Saanen camping ground. The number of participants grew steadily and, from 1968 to 1985, by which time several thousand were attending from many parts of the world, a large marquee had to be erected on the football field. In July 1985, after 25 years in Saanen, Krishnamurti announced the end of the Saanen Gatherings. He died less than a year later in California at the age of 90.

These explorations into the human condition were deeply meaningful to many, many thousands of people. They also added to the renown of Saanen. Some years ago we felt it was unfortunate that these events appeared to be fading from local memory so, in consultation with Stephan Jaggi of the Museum der Landschaft Saanen and with the enthusiasm of Rolf Steiger of the Menuhin Center in Saanen, we set up the exhibition, Krishnamurti in Saanen: 1961-1985.

This exhibition was held over the past summer and, I understand, will return to the museum for the period 14 December 2019 to 12 April 2020. What feedback have you had from the summer exhibition?

We’re delighted that many of the local people who visited the exhibition could remember the original talks taking place. Some had rented rooms to participants all those years ago or could recall their parents doing so. Some had attended the talks themselves. Others came to the exhibition from further afield, from Zürich and Italy for example. Many visitors took material away with them and some engaged in dialogue with us.

The exhibit displays 24 short quotes in English, German and French together with beautiful photographs of the region to make a virtual Krishnamurti Philosophenweg. Several visitors to the exhibition expressed a desire to see a permanent Krishnamurti Philosophenweg established in the Saanen valley, similar to the Yehudi Menuhin one. We would be pleased to support this if the commune were to agree to it.

Longer quotes are also exhibited in all three languages and visitors can watch extracts from videotaped talks and speak with one of us or another curator. Whatever a visitor’s inclination may be, the exhibition offers something to pique or further the interest in an ongoing journey through the central question: What is it about human consciousness that is affecting our lives and the world so drastically?

I’ve read that Krishnamurti did not want to be a guru or have followers. Why was this?

He was moved to observe, to explore and to inquire, together with others, ‘like two friends sitting on a bench or walking in nature and looking at life together’. The notion of trying to mould someone to evolve spiritually in order to achieve something was, to him, not only wrong-headed and distasteful but also bound to fail. The ego or ‘self’ cannot transcend itself, there is no esoteric knowledge, and there isn’t a fixed state to arrive at. Instead, there is learning. This requires interest in – and close attention to – our thinking, our feeling and our daily lives, as well as to humanity and all of nature. It requires inner questioning, doubting our many assumptions, discovering and dropping what is false. Anything else – like following someone or a set of ideas or simply believing that we’re one thing or another –, however comforting it may be, weakens us, denies our capacities and freedom and undermines our humanity. We need to see what is – without prejudice or wishful thinking, and at ever-deeper levels – because that is the only way to face facts.

Every day we read new reports on the effects of climate change. Krishnamurti did not feel separated from nature and was deeply moved by natural beauty. What do you think he would say about the immense challenges facing the planet?

As a species we’re living unsustainably, with cruel effects. Some might believe in a future of technological fixes but Krishnamurti would say (did say) that the problem is not essentially outside ourselves. It lies in our attempting to stand apart from nature and from each other. We’ve been reducing the interconnectedness and wholeness of life to an all-important ‘me’ and an exploitable ‘other’. The devastating consequences, both physical and psychological, can hardly be escaped. He was clear about this long ago.

To avoid deepening these crises we’ll need to work together on socio-political, economic, educational, technological and other levels. But unless we acknowledge our absolute oneness with nature and with each other, and live that way, effective solutions or the right balance will not be found.

Krishnamurti was interested in education and founded several schools, including Brockwood Park School in the United Kingdom. An extract from the Brockwood website states: “Begin by taking away punishment and reward. No grades, no comparison, no competition, no prizes.” This is an interesting approach but how does it fit with today’s competitive world where a student requires excellent examination results to gain a place in a prestigious university?

Education that cultivates competition is irresponsible. It destroys sensitivity, integrity, intelligence and compassion and promotes fear and cynical self-centredness. It undermines real relationship and sets us up for injustice and violence; it conditions us to become cogs in a deadly machine.

Krishnamurti’s approach to education is different. Many students from Brockwood Park and the other Krishnamurti schools excel academically and proceed to top universities. But the point is to love learning, not only when studying a certain subject but, much more importantly, in observing the whole of life, questioning assumptions, developing deep care for humanity and all other creatures. With profound observation, wholeness, care and self-knowledge at the heart of education, the Krishnamurti schools stand for a radical transformation of ourselves and of our chaotic world.

Guy Girardet